“People are mistaken when they think that technology just automatically improves. It does not automatically improve. It only improves if a lot of people work very hard to make it better, and actually, it will, I think, by itself degrade. You look at great civilizations like Ancient Egypt, and they were able to make the pyramids, and they forgot how to do that. And then the Romans built these incredible aqueducts, they forgot how to do it.” – Elon Musk

Indeed, the assumption that knowledge is immaculately preserved as humanity progresses is something of a fallacy. When neglected, carefully honed crafts and advanced technologies tend to fall by the wayside, oft erased from collective memory for generations. The delicate craft of global macro investing is no different. In this piece, I will attempt to draw a red thread through Justinian’s Plague, Three Mile Island, and the low-rate environment of the 2010s to illustrate just how vulnerable the art of macro investing is to the relentless passage of time.

Rome 250 AD

From the widespread use of cement to viaducts and sewage systems, Rome of 250 AD would have looked perfectly alien to a peasant in 15th Century England. So, pray tell, what happened? In short, we lost the ability to hand down the craft because the unexpected happened.

From the widespread use of cement to viaducts and sewage systems, Rome of 250 AD would have looked perfectly alien to a peasant in 15th Century England. So, pray tell, what happened? In short, we lost the ability to hand down the craft because the unexpected happened.

After a battery of brutal plagues hit the Roman Empire, decimating its labor force, and means to defend itself, Pax Romana gave way to a period of conflict, infighting, and decay. Eventually, the Empire pivoted east to Constantinople setting western Europe on a trajectory into the dark ages.

Justinian’s Plague in 541 AD was the final nail in the coffin. It ended up wiping out 20% of the Mediterranean basin, and plenty of knowledge with it, within just 6 years. It took Europe almost 1000 years to build back piecemeal to be back on par, technologically, with the Romans of yesteryear.

Nuclear Lethargy

The accidents of Three Mile Island in ‘79 and Chornobyl in 1986 elegantly highlight the same fallacy. Collectively, the environmental disasters sparked anti-nuclear sentiment that largely halted the development of new nuclear plants in their tracks. Today, nuclear energy is top of mind, only this time as the white knight in our energy quandary and drive to decarbonize.

The trouble is when folks down tools for a generation, knowledge dissipates into the ether and the savoir-faire of the craft lies in the hands of retirees and those that have since passed. It is exactly this issue of human capital and the continuous transfer of knowledge (or lack thereof) that the West is facing when it comes to rolling out new plants. Point in case: The Flamanville nuclear plant, which was due to open in 2012, is hitherto undergoing repairs as welders are still fixing mistakes discovered on the reactor’s cooling system performed by novice contractors (Great WSJ infographic on this story).

Macro Renaissance

But what does this have to do with discretionary macro managers? For our final example, I want to take you back to 1969, when a motley crew of Nobel laureates, MIT professors, and commodity traders banded together to form Commodities Corporation (CC). It was widely seen as the cradle of global macro investing. They methodologically created, stored, and handed down the craft of discretionary macro investing and risk management through generations of talented traders, some of who left to start their own firms, among them:

- Bruce Kovner of Caxton Associates

- Paul Tudor Jones of Tudor Investment Corp

- Louis Bacon of Moore Capital Management

Each of these legends, in turn, served as a launch pad for the next generation of macro managers. So long as there were dislocations in global markets, macro managers were there to play out sophisticated investment theses and in doing so incubate talent that would invariably fly the nest to launch a new shop. And on the cycle went.

Until something unprecedented happened, the 0% rate world that emerged from the Great Financial Crisis created a previously unthinkable environment of high correlation between asset classes coupled with low volatility (adieu, market dislocations).

Until something unprecedented happened, the 0% rate world that emerged from the Great Financial Crisis created a previously unthinkable environment of high correlation between asset classes coupled with low volatility (adieu, market dislocations).

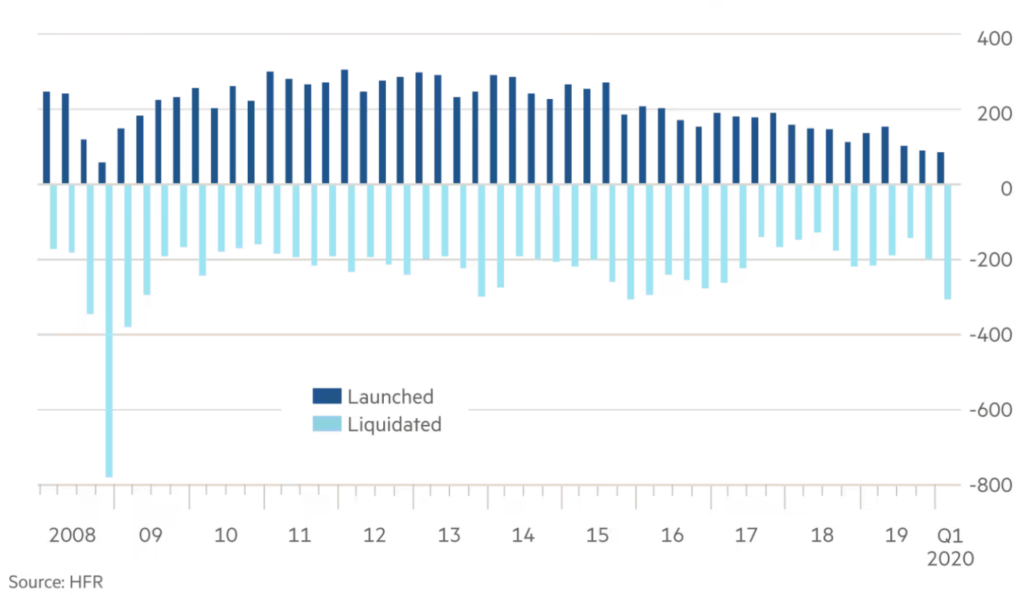

One needn’t look further than the number of new Hedge Fund launches vs. liquidations since 2011 to understand the ramifications of a 0% rate world: The rate of new hedge fund launches slowed, whilst liquidations picked up. A trend that was particularly pronounced for macro managers.

The irony is that with rates being hiked asynchronously across the board and inflation rearing its head again, the scene should be set for a new macro renaissance, with launches aplenty. Yet bewilderingly, it’s more difficult than ever to find (new or simply open) macro managers. Why is that? Did we forget how to make them? Not quite.

It would seem that the craft has suffered a “death by a thousand cuts”, confounding the already difficult launching environment of the 2010s. Among the more severe lacerations:

- Ironclad non-competes that made it exceedingly difficult for portfolio managers to set up a competing firm, often resulting in long protracted litigations

- The allure of multi-PM platforms and their sign-on bonuses that effectively snuff out would be launches in their conceptual stage

- Emerging managers being bought out by multi-PM platforms before they hit the proverbial 3-year milestone (e.g. Ex-Deutsche Bank FX Chief Shuts Hedge Fund to Join ExodusPoint)

- Existing blue chip names, returning external capital and pivoting to family office model (e.g. Soros Fund Management, Moore Capital Management, and BlueCrest Capital Management).

So where does that leave us? It would appear that we have a graveyard of ill-fated macro launches on one hand and a huge concentration of capital with a handful of hard-closed champions on the other. The interactive Sankey diagram below serves to map the genesis of macro managers, and where we are today (note: this is our best attempt at a representative picture, so if you do have some names we left out just let us know and we’d be happy to update the diagram)

Long gone are the days of mentorship and spinoffs. Welcome to the era of hard closed blue chip macro managers and fierce competition for talent, where investors’ options seem to be limited to either buying macro exposure via multi-PM platforms or scouring the globe to find unconventional paths from whence talent has emerged.

So, Did We Forget How to Make Macro Managers?

You’d be forgiven for thinking so, but we’re convinced otherwise. We’ve searched the globe, scraped the web, and shaken down some of our top contacts in the macro space to uncover the next generation of macro managers who we will be showcasing during our next event, the Agora Macro Dislocations Conference, in early December. We look forward to introducing the 6 macro managers we have unearthed, who will be presenting alongside our all-star lineup of guest speakers. To give you a taste of what’s to come, we are thrilled that:

- Philippe Khuong-Huu, Chief Investment Officer of Alphadyne Asset Management, will unpack the state of fixed income and broader macro markets with David Modiano

- Al Breach, Co-CIO and Lead PM of Gemsstock will be lifting the lid on macro opportunities in emerging markets in a fireside chat with Leopold Gasteen

- Steve Drobny from Clocktower Group will be sharing some pearls of wisdom on the evolution of the craft of macro managers in a fireside chat with Edouard Robbes

- Juliette Declerq, Founder of the esteemed macro research house JDI Research will be delivering the keynote on her latest thesis

Stay tuned, more to follow. Until then, if you’d like to attend, please register your interest as this is an invitation-only event exclusive to institutional investors.

The views expressed above are not necessarily the views of Thalēs Trading Solutions or any of its affiliates (collectively, “Thalēs”). The information presented above is only for informational and educational purposes and is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any securities or other instruments. Additionally, the above information is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for investment, accounting, legal or tax advice. Thalēs makes no representations, express or implied, regarding the accuracy or completeness of this information, and the reader accepts all risks in relying on the above information for any purpose whatsoever.